Piracy is as old as trade itself. When Spain and Portugal began sending treasure fleets carrying gold, silver, and goods across the Atlantic in the 16th century, it didn’t take long for pirates to appear. You might recognize some of the most famous names: Francis Drake, Henry Morgan, Blackbeard, John Hawkins, and others.

Some pirates resembled more like companies than the anarchic individuals you might imagine.

English piracy often took a special form: privateering, where privately owned ships were authorized by the Crown (via letters of marque) to raid enemy shipping during wartime.

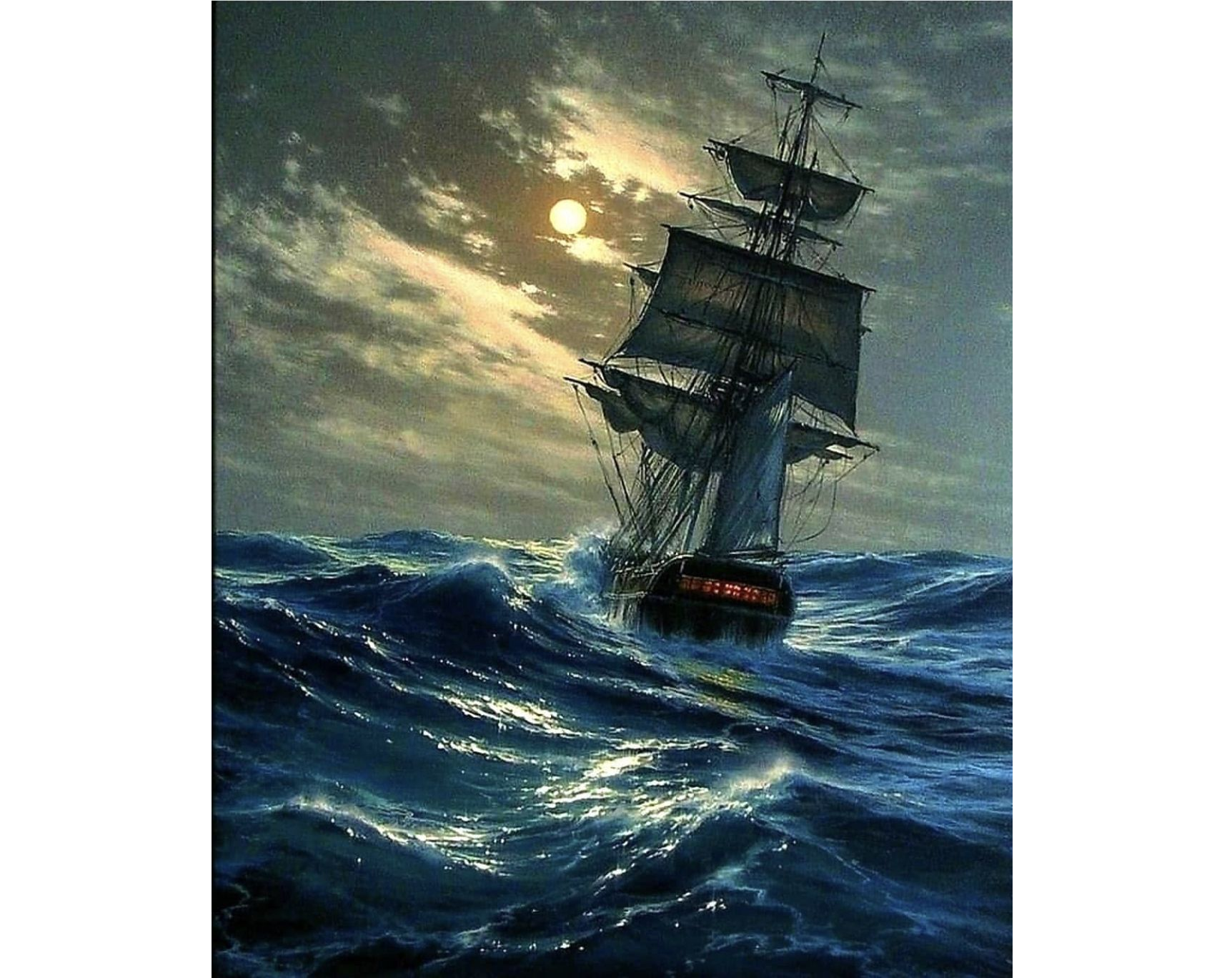

Marek Rużyk (1965, Polish painter) - Unrest at Sea

Marek Rużyk (1965, Polish painter) - Unrest at Sea

A new era of piracy

How countries, companies, and individuals attack and disrupt each other has changed dramatically: it’s more digital and complex. But the underlying incentives remain the same: steal value from others to enrich themselves.

If the space industry continues to develop as expected, it’s only a matter of time before space piracy becomes a real concept. All these expensive satellites and data centers orbiting look very juicy and largely unprotected!

What counts as space piracy?

I’ll use space piracy as a broad umbrella: extracting value from a space asset without authorization by taking control of it, degrading it, or coercing its operator. Some specific examples include:

- Service theft: using someone else’s satellite capacity (bandwidth, compute, sensing) without paying.

- Data theft: exfiltrating high-value data products (imagery, signals intelligence, proprietary processing outputs) by compromising the ground segment or the downlink pipeline.

- Ransom/denial: threatening to disable, deorbit, or simply make an asset useless unless paid.

- Signal hijacking: interfering with user links, spoofing signals, or impersonating a satellite to users on the ground.

- Physical capture or tampering: rendezvous and proximity operations, docking, attaching a device, or relocating the satellite.

Orbit changes the constraints, not the incentives.

Orbit changes the constraints, not the incentives.